Like any ship sunk in warfare, the Fetich Boulen might belong to a tale of seemingly impossible victory, or of unbelievable defeat, depending on what side of the battle it is told from. It might be the story of the heroization of Nikolaos Vóstis, governor of the ‘11’ torpedo boat which impressively sunk the Fetich Boulen, or of the seven Turkish lives lost to her destruction. It might belong to a longer, broader history of all the port of Thessaloniki has witnessed and endured, or mark the beginning of the chain of successes the Greeks would come to merit during the First Balkan War. This is the beauty of shipwrecks: their stories open the doors to so many others, coming from a variety of perspectives. What is a site of victory for some may be a graveyard by others.

Figure 1: Photograph of the Fetich Boulen between 1905 and 1906, (Istanbul University Archive, via WikiCommons).

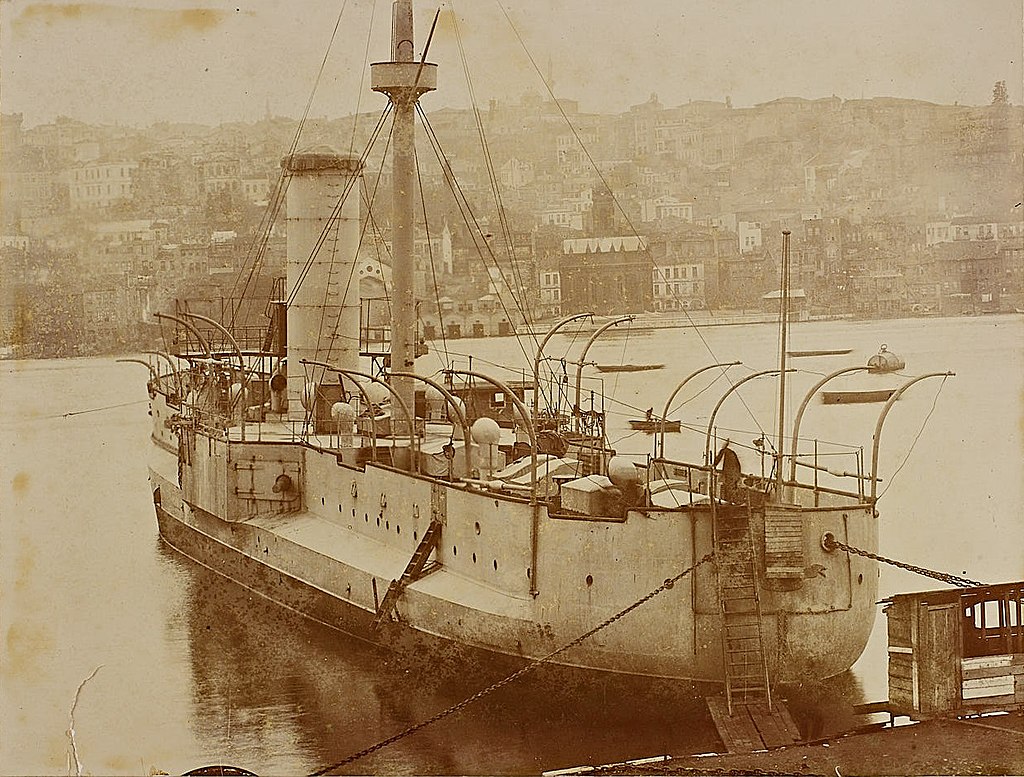

Figure 2: Report of the sinking of the Fetich Boulen in the Esperini Newspaper, October 21 (Old Style), 1912, (The Historical Association of the Balkan Wars).

Christened the Feth-i Bülent, the ship’s Ottoman Turkish name translates to ‘Great Victory’. It is both fitting and ironic to call it so, as she was indeed involved in a triumph during her lifetime. But her victory was not her own; rather it was achieved when she was unimaginably sunk by the Greek naval officer Nikolaos Vóstis. On the night of 31 October 1912, Vóstis governed and guided the ‘11’ torpedo boat through the minefield and the dark of the Ottoman-occupied port of Thessaloniki, from which he launched three torpedoes at a war-turned-barracks ship, the Fetich Boulen. Although one missed the boat and exploded in the quay, the other two met their target, causing her to capsize, while the 11 exited the port unscathed.

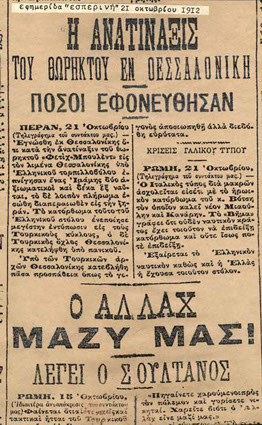

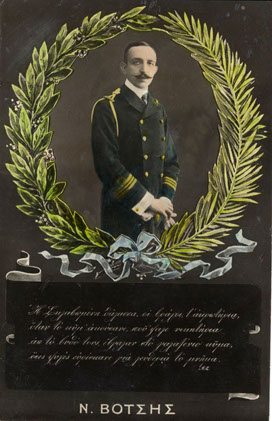

Figure 3: Lithograph postcard depicting the attack on the Fetich Boulen, with portrait of Nikolaos Vóstis, (Macedonian Heritage via WikiCommons).

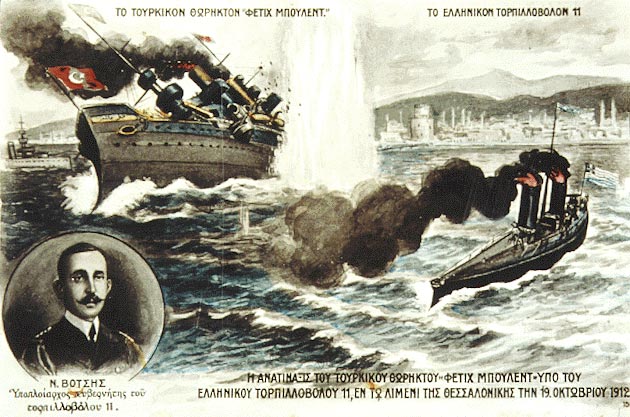

The sinking of the Fetich Boulen in flames and smoke was a common image gracing postcards, preserving the memory of the event forever. A portrait of Vóstis graces the bottom-left corner, his face stern but seemingly satisfied. For his destruction of the Fetich Boulen, following an impressive traversal the Ottoman-occupied port and minefield without a scratch to the Greek vessel and crew alike, Vóstis was venerated a hero and upgraded to Lieutenant Commander. The victory, commemorated though the display of the loot of the sunken ship atop Thessaloniki’s White Tower and later a bust of Vóstis himself, was less significant militarily than it was ideologically: the event boosted Greek morale and commenced a timeline of several Greek successes against the Turks that would later follow throughout the First Balkan War.

Figure 4: Postcard depicting a photo of Nikolaos Vóstis; caption reading: ‘The enslaved sea, the rocks, its cape when they heard that he was looking for victories from its bottom, they came out in the blue wave, all the souls that found the memory for freedom’, (The Historical Association of the Balkan Wars).

While Greeks celebrated the sinking of the Fetich Boulen, it inversely represented one of the many increments in which the power of the Turks was dismantled. Their loyal vessel served her time in the Ottoman navy and witnessed much of the tumult that characterised the Balkans and Black Sea during the latter years of the 19th century, probably not unlike the seven seamen who lost their lives during the attack. A veteran of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878 herself, the Fetich Boulen was British-built in the Thames Iron Works in 1868, a coal-powered casemate ironclad warship boasting four 9-inch guns and 3250 horsepower – almost three and a half times that of the most powerful road-going Ferrari. She was deemed ineligible for battle in the Greco-Turkish War, but was renovated instead of decommissioned and took her last position on guard in the Thermaikos area of Thessaloniki’s port. What remains of the Fetich Boulen and where she eventually lay to rest is less clear than her wreckage and its account of both victory and loss.

Figure 5: Painting by Rufin Sudkovsky of the Fetich Boulen in battle with the Russian Vesta steamer in the Black Sea during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877, (held by the Central Naval Museum of St. Petersburg, image via WikiCommons).

References

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships: 1860–1905. London.

- Langensiepen, Bernd & Güleryüz, Ahmet (1995). The Ottoman Steam Navy 1828–1923. London.

- ‘The Historical Collection of Balkan Wars’, The Historical Association of the Balkan Wars: http://www.balkanwars.gr/vithissi-tou-fetich-boulen.html.

[*] Issabella Orlando is a graduate of King’s College London, writer, diver and aspiring maritime archaeologist. Inspired by new discovery and the colourful world around us at present and in the ancient past, she aims to apply her interdisciplinary interests and background in Classical Studies to innovative archaeological research and cultural heritage management.