I am holding a fork in my hands. I look at it carefully while my mind drifts back into the past. The tainted metal is testimony to its age. I invert it to inspect the underside of the handle, just where it widens at the end. I see what I was expecting; an engraved Nazi eagle with the German swastika firmly caught in its claws.

The crew’s fork has survived to this day (photo: Vasilis Mentogiannis archive)

“I was very young, I think we were still at the lighthouse. I was crying and grandpa had nothing to give me. He got up, and a little later brought me this fork. I’ve kept it since then. I grew up and kept it with my good dinnerware,“, Mrs. Melou Foula told us. She is granddaughter of the man who had been the Psathoura lighthouse keeper during the war. She had been recounting a story from that terrible period back in 1942. I was driving my car back from Ermioni. It is a small coastal town in the Peloponnese and where I had met Mrs. Foula. It gave me ample time to reflect on the entire story…

Two years had passed since spending a pleasant evening with good company at Drosakides Tavern. Idyllically situated on the shores of Steni Vala bay on the island of Alonissos in the Sporades, we ate and chatted in the cool August evening air, as Greeks are fond of doing during the summer months. With us was Captain George Drosakis. He promised to take us to a place he had found while fishing near the lighthouse on Psathoura island, north-east of Alonissos. However, the weather became unfavorable. The days went by and we had to go back. The opportunity had slipped away. However, I did not forget – how could I? I remembered his exact description as well as all the technical details I had gleaned from my eager questioning.

“What do we know about this?” my Editor at the magazine asked. “Not much,” I replied. “Only the Captain’s description, that it is in very good condition and that he will help us find it.” The Editor looked at me with growing doubt. “Do you think it’s worth it?” he asked. “I think so,” I answered. “We also have a testimony from the lighthouse keeper. We know that the crew was saved and we know the type of aircraft. It’s a German light bomber – a Junkers-88.” The Editor just stared back. “We’ve never found an entire aircraft,” I added, hopefully.

Junkers-88, flying in formation (photo: Vasilis Mentogiannis archive)

“On another investigation carried out years ago off the island of Ithaca (on the Greek western seaboard), we only found the two engines and a small piece of the tail section of a plane. There are indications of two other planes near Piraeus, but we knew nothing else. The current lead was the best so far. “Yes, in my opinion it’s worth it,” I reaffirmed. “Alright,” he eventually replied. Preparations for our exploration could now begin.

Yianni Goulelis along with Droso Drosaki (photo: Vasilis Mentogiannis archive)

It was autumn when I arrived on Alonissos together with Yianni Goulelis. Our ‘man on the ground’, Drosos Drosakis was waiting for us at the port. We continued our journey and reached the bay of Steni Vala, which was to be our base for the next five days. “Is the boat okay?” I asked Drosos, “It’s not what we were expecting, but it’s okay,” he replied. “Anyway, the weather is very good and you can start tomorrow.” The boat was quickly loaded next morning and we were ready for departure by around nine o’clock. Friends and family were told that we expected to return by four or five in the afternoon. Cell phones have no signal so far away and on-board radios are often inaudible. “According to the Captain’s information, the aircraft is located at the northern point off Psathoura lighthouse at a relatively close distance,” I told Yianni on the way. He listened to me dispassionately. “The maximum depth is 32 meters and we have provisional co-ordinates, I believe we will not have any difficulty in finding it,” I continued. Yianni did not answer, he just continued to steer the boat.

The Psathoura lighthouse (photo: Vasilis Mentogiannis archive)

The Psathoura lighthouse is located about 22 nautical miles from the port of Steni Vala at the northernmost point of the Sporades island group. At the speed of 17 knots, it takes about an hour and a quarter to get there. Known as ‘The Eye in the North’, the area is quite dangerous because it is so exposed. However, the sea was calm for us, and we enjoyed the ride. After about forty-five minutes, we were able to discern the lighthouse for the first time. With GPS in hand, we set a course for the exact point described by the Captain. “Right here, hold!” I shouted. Yianni slowed the boat down. “Depth?” I asked. “Forty-four meters,” answered Yianni. I was puzzled. The depth should be thirty-two metres at this exact point. “Go on, until the depth gauge is reads thirty-two,” I told Yianni. We crawled forward until; “Thirty-two! Here we are!” Yianni confirmed before dropping anchor.

Once we secured the boat, we began our preparations for the dive. However, I sensed that something was wrong. Even though the depth was thirty-two metres, we can dimly see the bottom. Ordinarily, we would see nothing at such a depth. We splashed into the water, did a final visual check of our gear and began the descent. On reaching the bottom, our instruments read a depth of only nineteen meters. We looked at each other quizzically. Was the anchor dragging? Had we drifted into shallower water? More than forty minutes later, we had not encountered anything interesting, so we ascended. Back on the surface, we found ourselves having to fight against a strong current to get back to the boat. Fatigued, we climbed on-board and I immediately rechecked the boat’s depth gauge – it was still reading thirty-two metres. The anchor had not dragged. Getting back in the water for a quick inspection revealed damage to the underside of the boat. So, we decided on the obvious thing – to go back to the original location as described by the Captain. We weighed anchor and followed the GPS readings to return. However, the inaccuracy of the boat’s depth gauge presented us with a problem.

“What are we going to do?” asked Yianni. “We’ll tie my dive computer to a weighted line and drop it over the side. It remembers the maximum depth, so we’ll try to take some measurements,” I responded. It took a little time but we recorded a depth of thirty-four metres. So, we dropped anchor and prepared to dive again. After our descent, the depth was indeed thirty-four metres. A little further on, however, it dropped sharply to forty, which was inconsistent with the Captain’s description. We continued our explorations nonetheless. It was now around half past three in the afternoon and we were near the end of our fourth and final dive. With any hope of discovery on our first day almost gone, Yianni finally spotted something. Knowing that he couldn’t stay down much longer, he quickly tied the end of his decompression marker buoy to the object. He inflated the buoy and it shot up to the surface. Then he followed me on our ascent. He soon joined me on the surface. Hope had been rekindled. “What happened? What did you see? Tell me!” I asked impatiently. “I found a piece of cockpit canopy, and a short distance from an aircraft rudder, I think I saw the vertical one ” he replied. “Anything else?” I asked anxiously. “No, nothing else. It’s weird,” he answered. I could feel the hope fading. Thoughtful and cautiously optimistic, we began our return. The sun had fallen low and we were getting a little cold.

We recounted the whole story to Droso while taking our evening meal. “It can’t be,” he said. “It must be there somewhere,” he concluded. After eating, we formulated a plan for the following day. Using the buoy tied to the canopy as a reference, we would place other buoys to delimit four separate search areas. Drosos brings whatever we will need from his warehouse.

The next morning we loaded the boat with the extra gear we needed and set off. The weather remained wonderful and we reached the lighthouse quickly. We placed the buoys, taking care that they were as equidistant as possible. Nothing resulted from our first dive, but this did not dampen our initial optimism. However, the fourth dive marked by the last buoy also resulted in nothing. I was disappointed and began to think that we would never find it. It was already about two o’clock, and I didn’t know where else to look. Growing tired and desperate, Yianni and I sat in silence. We were surrounded by beautiful wilderness and the lighthouse stood steadfast in the distance, as if to challenge our resolve.

Yianni suddenly suggested searching from where he had found the canopy to the shallowest point we reached yesterday. “But we covered that area yesterday,” I replied.“We would have seen something, if it were there,” I concluded. “I’ll go,” Yianni insists. He looks determined. “If you have the courage, go,” I consented. We still had two full tanks of air. John was soon back in the water and I was left to look at the lighthouse alone. I was thinking that even if we found the aircraft tomorrow, there wouldn’t be enough time for a full investigation. I was even thinking about how I could justify failure to my magazine Editor when another of Yianni’s decompression buoys suddenly shot up to the surface. It wasn’t far away from the boat. That could mean one of two things; either the aircraft had been found, or he was in some kind of trouble. I quickly reached for my mask and fins. However, before I could make myself ready to dive, he broke the surface. He removed his respirator to reveal a broad smile. “I found it!” It was a moment of elation! I enthusiastically continued by preparations, but this time an underwater camera and extra lights became essential. I took a moment to ready myself to see what had only existed in my imagination until that auspicious day, then splashed over the side.

No matter how many years pass, the first image, the first moment when you encounter a wreck remains engraved in your mind forever. We were at a depth of 32 metres when right in front of us we behold the eerie sight of a silent aircraft on the dark rocky bottom.

Next one of the aircraft wings (photo: Vasilis Mentogiannis archive)

The location is surrounded by rocky outcrops which create a trough, the middle of which lay the aircraft. That must have been why we couldn’t see it earlier. We had passed near this point at least three times! We found ourselves right in front of the cockpit and commenced a quick preliminary investigation – confirming that the aircraft was basically intact. However, this was the second dive on the same tank for Yianni and he was running short of air. We fastened a rope to the wreck to be used as a drop-line the next day. Reeling in a strange combination of excitement and relief, we made our way to the surface.

By the third day, a little fatigue is beginning to show. However, our excitement could not be contained and we eagerly made our way back to our discovery. We followed the drop-line down and we are soon on site. We had formulated a plan the previous evening – to search the surrounding area and, most importantly, locate the small metal ID plate on which the serial number of the aircraft was engraved. The number would allow us to identify the aircraft and the crew. According to the instructions received from German historians, the ID plate should be on the right side, just below the pilot’s window. A second possible location is roughly in the middle of the instrument panel, inside the cockpit. The visibility was good, but cloudy weather above darkened the water enough to turn it deep blue at this depth, thereby reducing the amount of light available to us.

The remains of the cockpit (photo: Vasilis Mentogiannis archive)

I found it somewhat strange that the aircraft was not in as good condition as I had imagined. Its wings remained intact, but the end of the tail section had fragmented into small pieces. A lot of the cockpit had also disintegrated and some instruments, a crew seat and several other bits and pieces lay in front of the aircraft. We could not locate the metal ID plate because the area around the cockpit had deteriorated badly. On the off chance that the ID plate was still attached, we looked at any sizable piece of metal we saw scattered around. However, our efforts were in vain. Both engines had fallen off right in front of the wings. There were no propellers, which might have been the result of a forced ditching.

Everything apart from the main fuselage, part of the cockpit and some tail section has disintegrated (photo: Vasilis Mentogiannis archive)

A machine gun, magazines, a flare gun, some instruments and other objects are gathered so as to be recovered just before our last dive.

A flare gun (photo: Vasilis Mentogiannis archive)

A smaizer sub-machine gun immediately after it was recovered (photo: Vasilis Mentogiannis archive)

A lamp (photo: Vasilis Mentogiannis archive)

A seat belt buckle (photo: Vasilis Mentogiannis archive)

We returned to Alonissos in the late afternoon quite tired. I thought of the lighthouse keeper’s testimony and wondered. The weather had been good, they had ditched the aircraft successfully and the whole crew had been saved. So, why was the aircraft in such bad condition?

Interview from Giorgos Agalou, Steni Vala. 2-6-1996 / Alonissos

“During the Second World War, my father, my mother and I were residents of Psathoura. During that time, incidents occurred which shook our quiet and secluded life…

On the right, the lighthouse keeper Agalos Agalou, photo taken in Trikeri, Pagasitikos Gulf (photo: Vasilis Mentogiannis archive)

On the right, the lighthouse keeper Agalos Agalou, photo taken in Trikeri, Pagasitikos Gulf (photo: Vasilis Mentogiannis archive)

… The first occurred on May 27, 1942. It was a calm night with a full moon when we heard the noise of an aeroplane engine very close above our heads. A plane was circling around the lighthouse. The lighthouse was closed due to war and only lit if necessary by order of the government. For fear of bombardment, for at that time you did not know where it might come from, we went out and hid in the bushes. It was 2 o’clock in the morning, and the weather was good. We could clearly see a large plane circling. Suddenly, the engines cut out. We learned later that this was because it had run out of fuel. The pilot took it down low and ditched in the sea. It travelled some distance on the surface and then sank. During this time, the crew abandoned it very quickly with the lifeboat. My father and I shouted to them from the shore, and pointed to the place where they might come out. Indeed, my father, who was a smoker, lit several matches to guide them to the particular point on the coast. When they got out, they pulled up the dinghy, thanked us, and went to the lighthouse. There we asked them if they wanted to eat, and they answered no. They ate fresh onions from our garden instead, for fear that we might poison them. Then they washed themselves by pouring water on each other from the cistern using an old petrol can. Then they fell asleep, leaving one of their four on alternate guard.

From the left, Ourania Agalou (daughter of lighthouse keeper and mother of Foula Melos), Foula Melos (as a child), lighthouse keeper Agalos Agalou and his wife Morfoula (photo: Vasilis Mentogiannis archive)

From the left, Ourania Agalou (daughter of lighthouse keeper and mother of Foula Melos), Foula Melos (as a child), lighthouse keeper Agalos Agalou and his wife Morfoula (photo: Vasilis Mentogiannis archive)

… On the morning of the next day they asked us where they were, if there were partisans, and if they could go and join the other Germans. One of the crew was Austrian and spoke Italian. My father knew the language, for he had served in the Royal Navy. That’s how we learned the history of the plane. It was a Junkers bomber, heading from Tobruk to Sicily. On the way, however, they were chased by Allied planes. To escape, they set course for the North Aegean. Their fuel ran out above Psathoura and the plane was ditched. The dinghy they used to save themselves proved to be a divine gift for us. Many pairs of improvised shoes were made from the hard rubber – both for us and for our relatives. I took them in my little boat (the only way of leaving the remote island). Favoured by the spring bunatsa (good weather), we sailed to Kyra Panagia monastery. They were hosted by monks Benjamin and Athanasios, who were afraid because they had stolen and sunk a ship.

The next day, we made it to Alonissos. They were taken in by Doctor Tsoukanas. We spent the next day rowing to Skiathos, where the crew joined the German garrison. Obliged by the support from my family and myself, one of them gave me a picture of himself. He had written something on the back. When I was later caught by the Germans in a sweeping operation in the Northern Sporades, I showed this photograph to my captor and was saved. He stood at attention when he saw the photograph.”

(Giorgos Agalou was born in 1916, and was 26 years old at the time)

“My friends, Giorgos Drosakis from Alonissos and Lefteris Glynatsis from Kalymnos were sponge divers. They discovered the plane at a depth of 30 metres. The aircraft had sunk quite far from where it was ditched. Its condition was generally good. However, some parts had detached and were scattered around…“. From Kostas Mavrikis’ book “Ano Magniton Islands,” Alonissos 1997

The fact that the entire crew had been saved suggests that the aircraft was also preserved after ditching. So, the reason why the aircraft was in such poor condition still remained unexplained. The assumption that the aircraft had been dragged and destroyed by nets did not apply. The morphology of the seabed in the area means that fishermen do not trawl there. Fishing by dynamite was a possibility, but highly unlikely because of the depth. Explosive damage would have had to come from a depth charge – but that does not explain why the tail section appeared to have been shattered by impact rather than a pressure wave. Another hypothesis concerned intense seas and underwater currents since the area is renowned for both.

Objects are scattered everywhere in the wider area of the wreck (photo: Vasilis Mentogiannis archive)

We had to leave the next day. We returned the boat and thanked Drosos. Promising that we would return for a holiday one day soon, we boarded the ferry back to the mainland and departed. On our return, we immediately handed over our findings to the Air Force. Exposure and drying can facilitate corrosion after being in a salt water environment for so long, so it was essential that the preservation process started as soon as possible. Captain John Karantanis, Director of Support and Maintenance at the Air Force Museum, welcomed us before preparing the appropriate paperwork to receive the items. “A smaizer sub-machine gun, six magazines, a rescue flare gun, four instruments from the cockpit, bullets, a buckle from the crew’s seat belt, a radio lamp and a flare… that’s all. I will deliver them immediately to the maintenance and restoration crew,” he promised. “I will let you know as soon as I have any news,” he added.

Even during our return journey, I was preoccupied with the question of the aircraft’s identity. Fortunately, we had the exact date of the ditching, and that, combined with the type of aircraft, gave us a lot of hope of finding it in the records. We sent e-mails with all the information we had gathered – all we could do was wait patiently for any replies. In the meantime, we visited the Navy’s Lighthouse Service and asked for data on the lighthouse and the lighthouse keeper of that time. We found the lighthouse keeper’s register, but the lighthouse keeper’s log and reports were non-existent. As Lieutenant Dimitris Patsopoulos informed us, the records from that time were either lost or never written because of the war. But we persisted and after a series of phone calls, we found Mrs. Melos Foula in Ermioni. She was the granddaughter of the lighthouse keeper in question. She showed us old pictures and the fork which belonged to the crew. Unbelievable I think, a German warplane near Psathoura lighthouse, a family in Alonissos and now a fork in Ermioni. A fork which made the existence of the crew a tangible reality.

Ourania Agalou, today in Porto Heli (photo: Vasilis Mentogiannis archive)

With my imagination running wild, I couldn’t wait to check my messages each day. I desperately needed news about the crew, but there was nothing. I was pretty sure they would answer and that the infuriating delay was simply because they were yet to find something. I could only hope that they were still looking. Then the first message arrived. It was from Dave McDonald from New Zealand, an expert in aviation history. In a single sentence he told me that our plane appeared to be Ju-88 A-4, with a war production number of 140225 and insignia B3+MH. It belonged to Squadron 1./KG 54 (1st Gruppe, Kampfgeschwader 54), commanded by Captain Haso Holst.

3D model of Junkers-88 G-7a (photo: Vasilis Mentogiannis archive)

I immediately replied and asked him about the possibility of more details and if we could find the crew today.

At the same time, a second message from Germany arrives. Our partner there, historian Peter Schenk, confirms the identification. After consulting Radke’s book, Peter was in touch with us two days later. He told us all about Air Squadron 54. The following details are from genuine Luftwaffe Diaries.

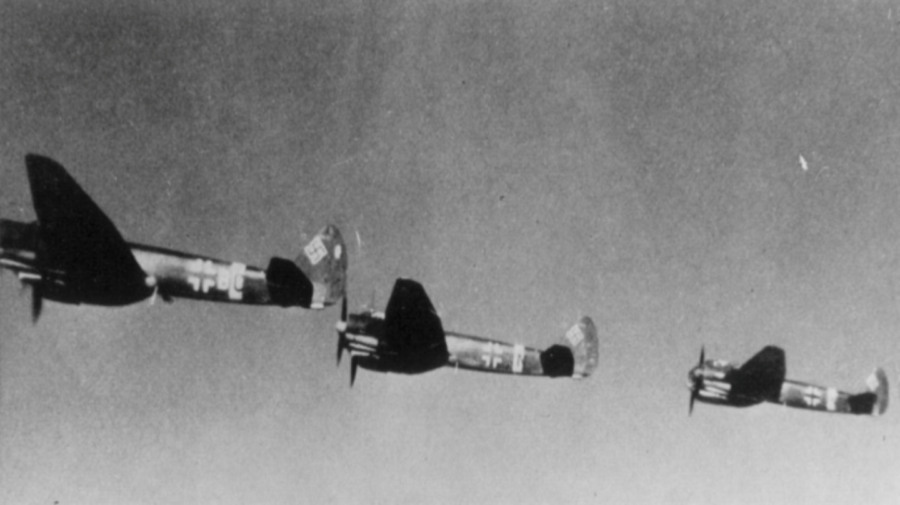

“On the 26th of May 1942, nine Junkers-88 took off from Elefsina airport at 14:00 hrs in order to bomb the Gambut and Abiar Zaid airports. A convoy of trucks carrying munitions were also hit. After refueling at Tympakio in Crete, five of the aircraft took off again on another mission, to bomb a convoy of trucks on the Bardia–Tobruk road at about 19:50 hrs. After failing to return, it was assumed that the 1st Squadron plane B3+MH with Captain Holst and crew must have ditched, since it would have run out of fuel. Communication had been cut off abruptly and no further information was available.”

“On the 28th of May, a report from the missing crew arrived, saying that they are well and making their way back to the Squadron.”

““On May 30th the crew arrived back at Elefsina airport. They reported that after damage to the aircraft compass while returning from their mission in Africa, they missed Elefsina airport. After many hours of flight, they ran out of fuel and ditched on May the 27th at 01:02, near the island of Psathoura (Northern Sporades). The plane sank but the crew reached the islet using an inflatable lifeboat and was saved.”

Junkers-88 taking off from Elefsina airport (photo: Vasilis Mentogiannis archive)

The research continued, with new evidence arriving daily. Air Squadron KG 54 was stationed in Italy in 1941. A detachment was sent to Elefsina with a further detachment later sent to Crete airdrome. Holst returned to Italy on July 21st, 1942. However, we did not find any additional information on the rest of the crew; bombardier Joachim Elsasser, radio operator Gerhard Richter and gunner Alfred John. All our efforts focused on being able to find one of them alive, until a message reminds us of the ferocity of war:

“On the 14th of October 1942, on an operation to Hal Far on Malta, Holst’s plane was shot down and crashed into the sea. The crew was lost.”

Incredibly, there is a sole survivor – Captain Holst. Attempts to track him down via Freiburg (the German archive service) and Germany’s telephone directories did not pay off. In our last communication with Junkers aircraft specialist, Belgian Philn Mertens, we were told that it would be extremely difficult to find him. However, he put us in touch with three German veteran pilots. When we told them our story, they promised to do everything possible to help us. The last message I received explains that they intended to publish a notice in the Jagger Blatt, a specialist veteran magazine. The notice will ask for information about Captain Haso Holst. The magazine will be published again this June, with a readership reaching as far as Australia! Time and fate will decide whether Haso Holst is meant to know that today, sixty-three years later, his plane has been found…

The Restoration Process

(By Dimitris Printezis, Lieutenant of the Air Force Air Force)

According to the Air Force and F.A.A. (Federal Aviation Administration) manuals, aviation metals, aluminum, steel and high-strength steels can be cleaned with acid solutions. These solutions consist of phosphoric and sulfuric acid. The relative amounts used depend on the condition of the metals and the level of restoration we want to achieve.

The preparation of restoration chemicals (photo: Vasilis Mentogiannis archive)

One of the properties of phosphoric acid when applied to metal is that it creates a protective film on the metallic surface in a process called phosphating. This stabilizes and protects the metal from future corrosion. Sulfuric acid reduces oxidation and rust. It also reacts with salt and vise versa, so they chemically cancel each other out. This means that the sulfuric acid used has to be replaced during the restoration process. A metal object that has been submerged in the sea for an extensive period of time will have high levels of infused salt, so a 20% phosphoric acid and 5% sulfate solution is used. This makes it very reactive against the salt. At these concentrations, there is a danger of alteration to the metal surface. To reduce this possibility, the object is only immersed in the acid mixture for a maximum of seven minutes.

After the first immersion, the object is rinsed with pure water and thoroughly checked. The procedure is repeated until the desired result is achieved. Physical methods are also employed; a soft or hard wire brush, a spatula (if the surface is flat), and a water jet to carefully strip away any marine encrustations.

Bullet immediately after restoration (photo: Vasilis Mentogiannis archive)

The belt buckle in very good condition after restoration (photo: Vasilis Mentogiannis archive)

The flare gun and a flare, after restoration (photo: Vasilis Mentogiannis archive)

Since the result is now clean bare metal, the next procedure is to apply wax or anti-corrosion oil and keep it in a controlled environment (temperature, humidity).

The star of the Luftwaffe

The Ju-88 was one of the best aircraft the German Air Force had during World War II. It was originally developed as a bomber and then evolved to perform a multitude of operation types, such as reconnaissance, night tracking, ground support, sea target attacks and the transport of supplies. Towards the end of the war it was also used as a flying bomb. With the exception of close dogfights, the Ju-88 was used to perform the most difficult missions in all theatres of the war.

It was powered by two twelve-cylinder in-line engines, one on each wing (Junkers Jumo) and was manned by a four member crew; a pilot, a bombardier, a radio operator/gunner, and a gunner. It was equipped with four machine guns (depending on the version) and capable of carrying a 2,000 kg bomb load. It had a wingspan of 20 metres and a fuselage length 14.40 metres. It could develop a maximum speed of 470 kilometres per hour.

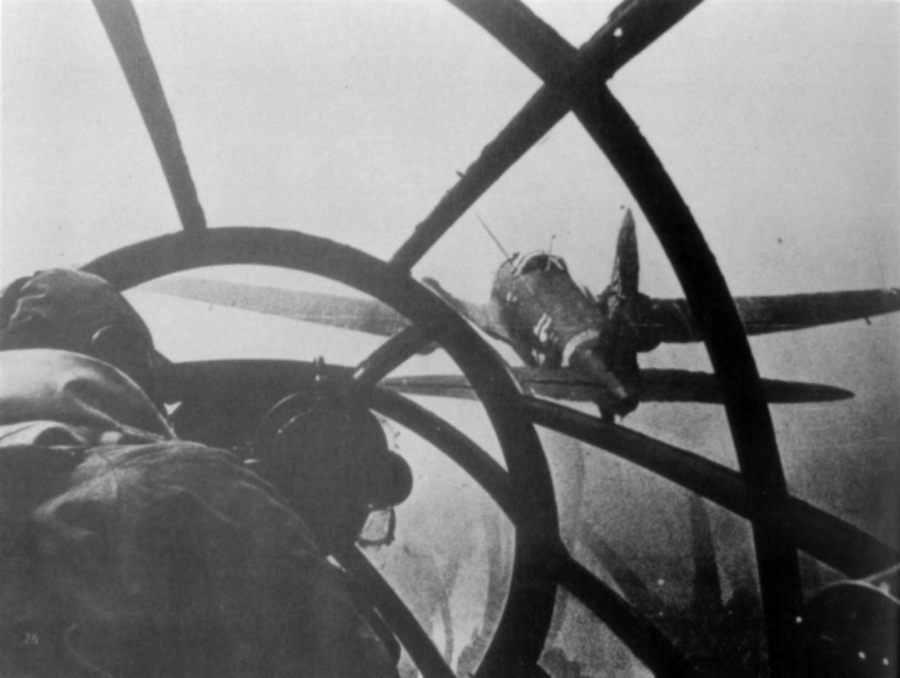

The position of the front gunner in a Junkers-88 (photo: Vasilis Mentogiannis archive)

The first production Ju-88 flew on September 7, 1939 and by the end of that year, a total of 69 aircraft had been built. Although it was initially designed as a fast light-bomber, it subsequently evolved to play different roles. Total production reached 14,780 aircraft, including 104 prototypes. 10,774 were bomber/reconnaissance versions and the rest were fighters. The night fighter version destroyed more Allied bombers than all the other German aircraft in total. It was one of Luftwaffe’s most valuable planes during World War II. Known as a reliable aircraft, it was deployed in all theatres of the war with great success. It was the distant progenitor of today’s multi-role aircraft.

The 4th Air Fleet consisting of about 1,200 aircraft was deployed in the Balkans. III/KG30 carried out several raids in Greece under the 8th Air Corps. The squadron had several successes against the British Navy in Crete and North Africa. Lehrgeschwader 1 Wing was the main unit in the Mediterranean Sea until 1944.

Bibliography: Aviation History, Yannis Varsamis

Psathoura

The northernmost islet of the Northern Sporades, Psathoura has an area of 771 acres. Its highest point to the north is only fourteen metres above sea level. Since construction in 1895, its 25 metre high lighthouse has towered over the island. A large wooden cross can be seen nearby. It marks the final resting place of George Fotopoulos, Chief Musician of the Greek Navy. He retired to the island after his discharge.

A sliver of Earth, in the middle of nowhere, the Psathoura lighthouse (photo: Vasilis Mentogiannis archive)

Some researchers identify the island as ancient Eudemia. The pieces of stonework scattered on the island are testimony to habitation in ancient times. There is an underwater volcano near the island. As Samson notes, the southern part of the island has suffered subsidence, because the ruins of houses and coarse vessels can be seen in the sea. To travellers, it is known as Larsura, Arsura, L’ Arsura, Laazar, I. Plane and I. Plane – Arsura.

Greek Lighthouse Number (AEF) 6160

A circular tower 25 metres high with a house for lighthouse keepers. It has a focal length of 40 metres. The lighthouse was first operated in 1895. Using oil as a source of energy, its continuous beam had a range of 19 nautical miles.

The Psathoura lighthouse (photo: Vasilis Mentogiannis archive)

The lighthouse was erected by the French company Cenerale Des Phares De L Empire Ottoman for the Ottoman Empire. Along with thirty-one other lighthouses, it was acquired by Greece as territories were repatriated.

It remained inoperative during the Second World War, but with the restoration of the lighthouse network, it became functional in 1945. In 1987, its oil burning machinery was replaced by a solar power source and the lighthouse became fully automated. It emits a white flash every ten seconds. Its beam reaches 17 nautical miles.

Navy / Lighthouse Service

[*] Ross J. Robertson is an Australian who has lived in Greece for the past thirty years. He has a BSc (Biology) and is an EFL teacher. He is the co-owner of two private English Language Schools and instructs students studying for Michigan and Cambridge University English Language examinations. He has written various English Language Teaching books for the Hellenic American Union (Greece), Longman-Pearson (UK) and Macmillan Education (UK). He published his debut novel (fiction/humour) entitled ‘Spiked! Read Responsibly’ in 2016. Moreover, he has written several spec screenplays and a number of newspaper articles, including an extensive series on the 75th anniversary of the WWII Liberation of Greece. A keen AOW and Nitrox diver, he is also a shipwreck and research enthusiast and has written features for UK Diver Magazine, US Diver and the Australian newspaper, Neos Kosmos. Ross continues to combine his expertise in English with his love of storytelling and local WWII history to produce exciting materials.